Breaking Promises

Main Points

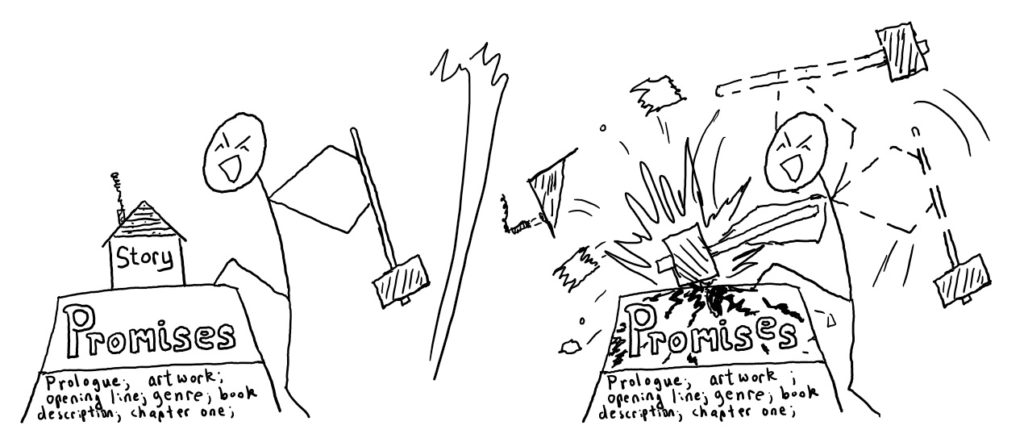

• Know your promises and keep them–promises are the foundation of your story.

• Promises are made in the cover art, marketing, a book’s description, the prologue, the first line, first chapter, and all throughout the book.

• Breaking promises breaks the foundation of your story and induces rage.

• So long as you’re upfront with your promises, you can do just about anything.

• Sometimes keeping promises is a gray area, but breaking them rarely satisfies readers.

Introduction Of Oblivion and rage

The worst movie I’ve ever seen, or at least the only one that gave me fits of anger and made me want to demand a refund, is Oblivion with Tom Cruise and Morgan Freeman. The reason I got so angry was one concept: broken promises.

***Spoilers follow***

I was fascinated by the premise in the trailer–it’s been years since aliens invaded mankind; after a brutal Pyrrhic victory, the earth is uninhabitable, so humanity leaves to find a new homeworld; the only remaining humans are clean-up crews taking the last of earth’s resources before they join with the fleet. The rest of the trailer showed intrigue, the surprise of other surviving humans, shots of the aliens, and I was hooked! The premise was innovative and gripping. I wanted to see that movie.

What I got was a mid-movie reveal that turned the premise on its head. Instead of following through with the interesting premise, the movie became a stereotypical alien invasion film complete with the magic bullet at the end where the good guy destroys all the aliens by killing the mother ship. The aliens in the trailer weren’t even aliens at all, just humans in weird suits! It turns out the alien war is still ongoing and the main hero is a clone being used by the real aliens. Learning the truth, the main hero joins the surviving humans and fights off the aliens.

I was horrified, shocked. This wasn’t the movie I wanted to see. This wasn’t the movie I was promised! The trailer was full of lies! And that betrayal induced rage.

Looking back, I should have known better. The trailers did hint at the reveal, so it was partially my own fault. But the disappointment and rage stuck with me (I still want to see the movie I thought I was going to see). The lesson about breaking promises stuck with me as well. Promises are the foundation of your story. Everything else depends on those promises.

Breaking Hearts More rage

An important example of this comes from Brandon Sanderson. In one of his lectures, he mentions a story about a fellow author who wrote a fantasy novel with the intention of turning the genre on its head at the very end. The author thought he was doing something brilliant, but as Sanderson pointed out, there are lots of problems with this approach: first, those who would be interested in something like this won’t read the book because it’s initially promised as a generic fantasy; second, those who are interested in generic fantasy will be gravely disappointed at the end because it completely breaks its promises. Who’s satisfied? How likely are readers going to buy the author’s next book when he betrayed their trust? Not surprisingly, the book didn’t sell well.

Sanderson took the right approach with his Mistborn series. When he decided to flip the fantasy genre on its head, he put it on the back cover. When I first saw his book for the first time, it had questions like, “What if the hero of prophecy fails?” and “What if the Dark Lord had won?” It intrigued me and these promises were kept from page one. It’s clear the Dark Lord has won and some new characters are fighting against him. And it works brilliantly. The previous author broke the foundation of his story while Sanderson set his foundation up right.

The point here is you can do anything you want, you just have to know what promises you’re making and not break them. George RR Martin is infamous for killing off his characters, especially the ones you like. This is a broken promise in most books (where you expect the protagonist to eventually win) but he does it masterfully. “I’ve been killing characters my entire career . . .” Martin once said in an interview. “When my characters are in danger, I want you to be afraid to turn the page (and to do that) you need to show right from the beginning that you’re playing for keeps,” (https://simple.wikiquote.org/wiki/George_R._R._Martin) The promises that he specifically makes are kept. It’s why it works.

Gray Areas Making and breaking promises

Sometimes, it’s difficult to know what promises to make. Dan Wells is an example of this in his book, I Am Not a Serial Killer. It’s an incredible book about a teenage sociopath who thinks he might be a serial killer. When killings start happening in his small Midwestern town, he has to unleash his killing potential to save those around him. Sounds great right? An intriguing thriller with a high-schooler version of Dexter. There’s only one issue, though. The killer is actually a demon. The book has some supernatural elements but the description gives no indication of that. It’s a great shocker or a great disappointment. Wells has said he still gets angry emails from people who expected an interesting thriller and got a paranormal thriller instead. It’s a broken promise, but a much smaller one compared to the other ones discussed. To be fair though, Wells does include some tips early on in the book that there’ll be supernatural elements later. Did he make the right choice in keeping it out of the description? It’s his book, so I’d say he did. But it can absolutely be a gray area at times.

How are promises made? How do we know which ones we need to keep and which we can break?

The initial question is easy. The latter is more difficult. I’ll use Twilight as an example in parenthesis since it’s well known (though problematic for its own reasons). Promises are generally made in advertisement–summaries, artwork (Twilight’s cover is dark and moody; the offering of an apple is evocative of Adam and Eve and forbidden knowledge), trailers, taglines (Twilight‘s: “If you could live forever, what would you live for?”), blurbs, the book description on the back, and especially within the first few pages. Prologues are often used as promises (Twilight begins with a tense scene that happens in the future and whets the appetite for what is to come; Meyer fulfills this promise when the scene happens later on and it’s exciting because it’s a fulfilled promise). The genre typically has some sort of built-in promises: romance books are going to have romance and will end happily (especially if the covers are pink); most children’s books are going to end happy; fantasy books will have a sense of wonder and adventure; etc. Some books (like Sanderson’s) ask a question of the reader. There can even be different promises made in the beginning, middle, and end of the book (especially promising toward sequels if applicable). In essence, almost every aspect of a book makes a promise to the reader.

It is paramount that you know what promises you’re making. Are you promising action from your prologue? Are you promising mystery? Are you promising romance? Are you promising happiness? Are you fulfilling these promises? If so, how long does it take to start fulfilling them? If not, why not?

When should you break promises? That part is tricky. I can think of very few circumstances where breaking promises actually helps the readers. If you know of any, please comment them down below. The one thing I can say about breaking promise is if you’re going to do it, first know what promises you’ve made. Are your readers going to be happy with the broken trust? Will it make them want to read more of your work? Would it make you or your best friend want to read more? Odds are breaking promises probably won’t help and it’d be far superior to keep them.

But what about you? What promises are you making with your stories? What are the most interesting promises a book, a movie, a game has made to you? Have any broken promises left you angry? Have any broken promises made you happy? I’d love to read about them.

5 thoughts on “Breaking Promises”

I enjoyed Oblivion, but I never saw the trailer. I was annoyed that Morgan Freeman had major billing but was barely in the movie.

The recent Marvel movies have generally done a good job of keeping the promises of the trailer (or the trailers promising the tone of the movies), especially Thor: Ragnarok and Guardians of the Galaxy 2. (However, Thor: Ragnarok’s Doctor Strange appearance was really short, and less involved than I expected.)

One of the all-time most perfect movie promises made (also a Writing Excuses example) was Raiders of the Lost Ark. The mini-adventure at the start tells you everything about the movie: Indy goes into places with unexplained but still working traps, faces danger, secures the artifact, Belloc takes it away, and in the end, Indy basically loses (but survives to raid another site later). But it’ll be a lot of fun along the way.

Imagine if it had started in the university, with the first quarter hour or more being the whole classroom/military intelligence/flights, and the first real action was the bar? The tone of the second half of the movie would be quite a turn from how it opened, and there might even be a lot more irritation that the Ark is basically buried at the end and Indy walks away with nothing.

Great examples! Raiders of the Lost Ark in particular. Masterful job of promising the rest of the movie. You’re right it would have been a much more different movie if it’d started out with the university scene.

I think that without the first tomb and the unexplained but highly adventurous traps, it would be a much harder to buy all the snakes and mummies doing their crazy stuff in the Well of Souls, and the viewer wouldn’t have been as perfectly set up for the tone of the action set pieces.

Goldfinger was the same way. The director said that most of the purpose of the pre-credits sequence was to prime the audience to sit back and roll with the zaniness of the adventure to follow. (I mean, c’mon, once you’ve bought Bond with a duck on his head, stripping off a diving suit to reveal a tux, and walking into a bar, smuggling gold via car ornamentation becomes normal!)

I should add that if you got a Bourne Identity-style adventure after that pre-credits sequence, it wouldn’t work. The tones clash too much. So in that sense, both Raiders and Goldfinger are making and fulfilling exactly the promises they need to.

Great points! The pre-credits definitely should set up the rest of the movie or book!

Comments are closed.