Comparing to Others

Main Points

• Comparing your work to others can be inspirational and disheartening.

• There’s a gap between our tastes and our work (initially); we need to keeping striving until our work matches our tastes (Ira Glass).

• Compare apples to apples–similar experience and capacity (the number of people working on a single book).

• By comparing, we can learn what we have to fix, what’s out there, learn by immersion, and find inspiration.

• Comparing can bring false hope: what worked 20 years ago might not work today.

Introduction

Comparing yourself artistically to someone else can be utterly devastating, enlightening, or somewhere in between. I’ve spent plenty of time reading other’s books and walked away completely wowed, wondering if I’ll ever be as good. It can be disheartening to compare how far I need to go, but heartening in how far I’ve come. The question remains, should we compare ourselves to others’ work? Are there potential dangers or benefits to comparing ourselves? Any guidelines to do so? Like most things, comparisons can be good or bad. Here, I’ll dive into what I think are the best ways to compare.

The Brutality of Comparing The gap of taste and quality

Comparisons can be difficult because we have high tastes but may lack the skills to produce things at that level. I learned this from Ira Glass, an incredible radio personality who’s worked for years in broadcast. Though the quote is long, it’s worth the read:

Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know its normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/309485-nobody-tells-this-to-people-who-are-beginners-i-wish

I love his point about the gap. You reason why you may think your art is crap is the same reason you recognize good art. Your taste. An important point is this gap is widening as time marches on. Storytelling has become richer, more technical, more creative, better as more and more fiction is produced and we have new markets and forms of media. But it doesn’t mean we can’t jump in and learn how to become great creatives ourselves. It does mean that the gap may be wider than before.

Comparing Apples to Apples No oranges allowed

One of the most common characteristics I’ve seen in experts is they make things look insidiously easy. Whether playing the piano, playing sports, writing fiction, programming, making movies/paintings/or-whatever, they make their work seem effortless. There’s an old adage that goes “Amateurs practice till they get it right; professionals practice till they can’t get it wrong.”

But while it may seem like it’s effortless, what we don’t see is the amount of time they put in before the final product. When we compare ourselves to these experts, we need to make sure we’re doing it on an even playing field. This is valid on two levels:

(1) Comparing timelines/experience. I had a leader who related he met a bunch of young women who were disappointed they weren’t as capable as an older and well known female leader in our organization. He pointed out that this leader was 80 years old and had approximately 60 years more experience than these young women. He then counseled us that if we were going to make comparisons, we should make them appropriately. He told the women that if they were going to compare themselves, they should compare their current 20-year-old self with the leader when she was 20 herself. Any other comparison is simply unfair.

It’s not just an age thing, it applies equally to experience. If you’re 40 years old and just started writing, it might not be useful to compare yourself to a 30-year-old who’s been writing for 20 years. There’s an enormous experience gap. Tim Hiller wrote, “Don’t compare your beginning to someone else’s middle, or your middle to someone else’s end. Don’t compare the start of your second quarter of life to someone else’s third quarter.” When we compare, we need to make sure it’s as apples to apples as we can instead of apples to oranges.

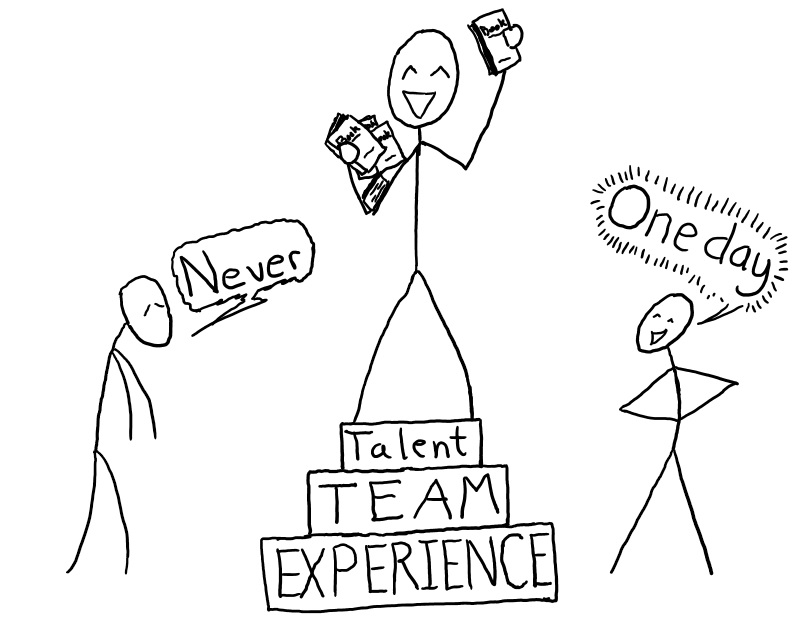

(2) Comparing capacity. Similarly, it might not be appropriate to compare our work to a final product that’s been traditionally published. After all, that book has gone through numerous story editors, line editors, marketers, etc. In fact, there are so many people involved in traditional publishing that the author only gets paid around 10% of the final product (meaning everyone else’s contribution is valued at 90%). It’d be insane to compare my solo work to an entire team’s worth without accounting for differences in numbers. It’d be much more useful to compare my submission draft with the author’s submission draft before it went through all the professional edits.

Most the time, that’s not possible as we generally only see the final product. However, the point still remains. If you really want to picture how your book stacks up against a famous author’s, you need to imagine yours with similar levels of professional editing or imagine their final book stripping away all of that. It makes a huge difference to have a whole team working on a book versus just doing it solo.

There’s one important exception I found for this, and it’s Brandon Sanderson’s Warbreaker. Sanderson publicly made all the versions of his novel available for free on his website, including the first draft, versions throughout, and (more or less) the final product. Comparing your own work to one of his earlier drafts might be more useful (accounting for his level of experience of course).

(https://brandonsanderson.com/books/warbreaker/warbreaker/warbreaker-rights-and-downloads/)

Learning from Others The case for comparing

As Ira Glass stated, our taste is what gets us in the game, gets us wanting to create art ourselves. So comparisons can help us:

(1) You can’t fix what you don’t know is wrong. Reading other people’s work can highlight your own weaknesses or strengths. Additionally, you can adopt someone else’s strength and avoid their own pitfalls.

(2) Know what’s out there. You don’t want to write something someone else has already written. While you can’t guarantee you won’t (most stories are derivative of something), you should at least have some knowledge of what you’re getting into. E.g. if you want to write zombie fiction, it’s a good idea to know what’s already popular in the zombie world and add something unique of your own. If you want to write a book about a boy who learns he’s a wizard and goes to magic school, you’ll have to make it different enough from Harry Potter.

(3) Learn by immersion. If you read good writing, odds are your writing will improve. It’s like how surrounding yourself with happy or successful people tends to make you happier and more successful. One exercise I’ve read about but haven’t tried is copying part of a great author’s work, word for the word, the thought being that doing so will help train your writing skills. An application of this is the Hemmingway Editor, which helps trim down writing into powerful Hemmingway-esque prose (http://www.hemingwayapp.com/).

(4) Find inspiration. There’s plenty of great inspiration you can take from comparing your work. I’ve seen loads of shows that I loved and wanted to write something similar to them (same kind of setting, same themes, similar characters, etc.). And I’ve seen plenty of shows where I was so disappointed that I wanted to write a better version. Case in point, I was so frustrated with Anakin Skywalker’s turn to the dark side that I wrote my own novel with a similar journey. I don’t know that it’s better, but at least I got a lot of experience and fun out of writing it!

A little ditty that I found when researching this topic was “Compare and despair” should be changed to “admire and inspire” (Creative Types: How to Stop Comparing Yourself to Others). We can be inspired by how authors write interesting characters, great action, thrilling pace, or whatever we’re looking to improve.

Dangerous Comparing When the old no longer works

Comparing can be fraught with dangers: it can be discouraging for one, and it can give us false hope. I recently read the first book in a series that came out in the early 2000’s. I didn’t like it. I didn’t think the writing was very good and I saw a lot of flaws. But it was published and has since become a successful series. A part of me became hopeful reading it because if that book was published, there’s hope for me yet! The problem with that thinking is (1) this was the author’s first book and he’s since improved, and (2) the entire market has improved. What worked 20 years ago might not work today. Many authors have stated that what got them into the publishing world might not work today, simply because tastes have evolved.

A great example are classic works. As much as Les Misérables is an incredible read, it wouldn’t get published today if Hugo wrote it as is. The tastes have changed, the bar has moved, and what was good-enough to be published yesterday might not be good-enough today. Poetic fantasy like Tolkien (typically) doesn’t work now. So we need to keep that in mind when writing and seek to understand the specific bar we want to reach.

Conclusion Finding the good in comparisons

As I see it, comparisons can be helpful. They can tell us where we need to go. They can give us inspiration and show us what’s possible. Comparing can also be utterly depressing. But when we account for things like experience and capacity, we can compare without completely going into despair.

But what do you think? Is comparing yourself to other creatives useful? Disheartening? Inspiring? Let me know below!

4 thoughts on “Comparing to Others”

How wonderfully constructive!

Thanks, TH!

Joanna Penn warns against “comparisonitis”, which is her term for the destructive form of comparing to others. She frequently emphasizes that we’re all on our own, individual creative journeys. My goals are not necessarily yours, nor are yours necessarily mine (nor are ours necessarily hers). Same for the journey itself — even if the end goal can actually be phrased identically, we’re each forging our own path, at our own speed, in our own way.

We can learn from others’ journeys, we can try to emulate their successes. A lot of the process is discarding the things that don’t (or won’t) work, and instead looking for the pieces that might.

I think Chuck Wendig pointed out that virtually all writing advice is “this is what worked for me”, but often elevated to “the one true way” pronouncements.

As you note, where comparison is useful is where it is non-competitive. Someone else is really good at something you want to be good at? Dissect their work, figure out why it works for you, and figure out *your* way of closing the gap. (Don’t necessarily just copy what they did.)

One place where it’s destructive is if you start tearing up your own, functional process solely because someone else did it some other way and it worked for them.

Observe, adapt and adopt, and improve.

Perfect advice! Thanks I.M Bonetti! It’s super important to understand that there’s no “one true way” to writing (or any other artistic endeavor).

Comments are closed.