Proofing

Main Points

• Proofing your own work is fraught with difficulties: we’re too close to our work, our minds correct small mistakes, and above all, proofing can be boring!

• Many techniques exist to improve proofing: make your work unfamiliar by changing the font or background color, read it aloud with foreign accents and/or pencil taps, print your work out, use software (like Grammarly), get fresh eyes to look at it.

Introduction

Making sure your writing is without error can be a daunting task especially after putting so much heart, love, and care into it. Proofreading can be a tedious drawl, boring and dull. Is my spelling correct? Is my grammar correct? Does it all sound right?

I’ve struggled with this throughout my writing. I lean towards the philosophy of ‘write fast, correct later’ which means I make more mistakes than my counterparts. However, I’ve picked up several tools that have helped me along the way. While I still struggle more than others in my writers’ group, I’ve made significant improvements.

But first, why is it so hard to catch our own mistakes? Turns out we all have enemies we struggle against.

Fighting Proofing Mistakes Enemies at the gates and within

The power of the mind. There’s an old forwarded email that goes something like this: “Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm.”

The email is problematic for a few reasons (see here for a thorough treatment: https://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/people/matt.davis/cmabridge/) but it shows an important point: we can read completely misspelled things and still get meaning out of it. More than that, the mind can actually create missing words for us so we don’t lose our pace of understanding. This leads to our second enemy.

We know the meaning we want to convey and are blind to our actual writing. One article puts it this way: “The reason we don’t see our own typos is because what we see on the screen is competing with the version that exists in our heads,” (https://www.wired.com/2014/08/wuwt-typos/). As writers, we know what we want to accomplish and we assume we’ve already accomplished it. Why? Because . . .

Our thoughts move faster than our fingers. I’ve often gotten to the end of a sentence while writing thinking “I’ve done a perfect job” only to realize I left out a bunch of words. Why? In my mind, I’d already moved on. I write between 60-80 words per minute. Average people speak about 100 words per minute (https://wordcounter.net/blog/2016/06/02/101702_how-fast-average-person-speaks.html). What about our thoughts? They’re more like a few 1000 words per minute (https://listenlikealawyer.com/2015/09/24/speed-of-speech-speed-of-thought/). Even if the numbers are wrong, the point remains: we write slower than we speak and much slower than we think. If we let our thoughts go off on their own, our words get left behind. This especially happens when I get into a state of flow, whether writing or reading. Because I’m living the experience, I’m not cognizant of the words going on and I don’t realize when I make mistakes.

We’re too close to our own work. This plays into all the others, but basically we think we’ve done a good job because it’s us! When you read someone else’s work, you’re much more likely to find mistakes than in your own. It’s like the fish in water problem: if you’re surrounded by water, do you know you’re in it?

Muscle memory gets in the way. Sometimes our fingers think they know what they’re supposed to type, and they type something we don’t want them to.

Boredom makes us not pay attention. This is by far one of the hardest issues to contend with. The mind craves stimulation and proofing our own work is simply boring. How many of us have read something then had our mind wander only to come to the end of the sentence, the paragraph, or the entire article and wonder what we just read. We got bored. If it’s dense (which proofing your work often is), it takes great mental strain to stay focused. This is the same problem that faces drone pilots (https://newatlas.com/uav-pilot-boredom-mit/25014/). Boredom breeds mistakes. We pass over errors, miss simple things because our minds are wandering.

Fighting Against Our Enemies Winning battles and making progress

So how do we combat our natural enemies to proofing? Here is a list I’ve picked up from other authors, friends, and articles. Essentially, we have to mix it up to the point we can trick our brains to slow down, pay attention, and look for trouble spots.

Read aloud–vocalizing forces us to think differently. It won’t catch ‘their-vs-there’ but it will catch a lot of mistakes.

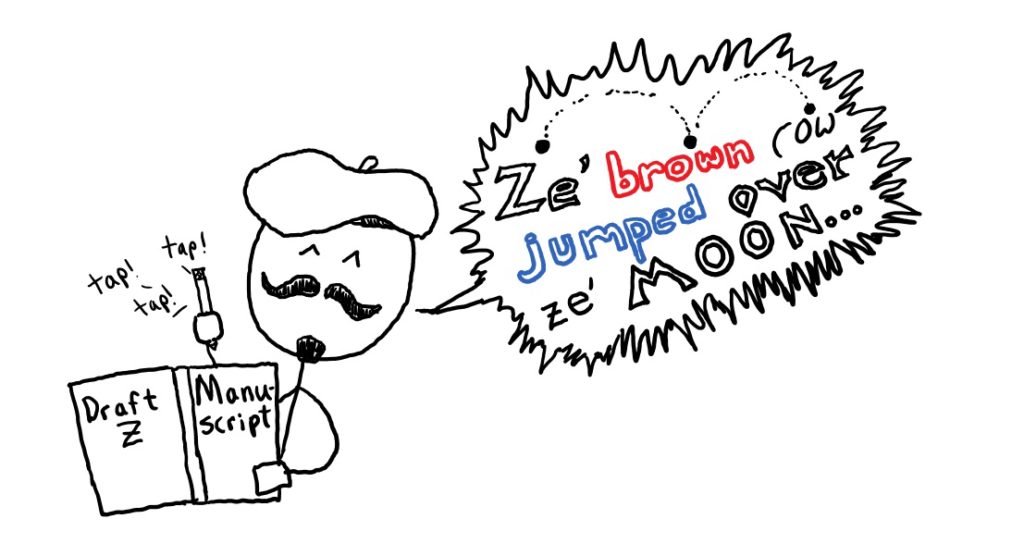

Tap each word with the end of a pencil individually as you read–this is like those sing-along songs with the bouncing dot. This significantly slows down reading and forces you to contemplate each word.

Read in another accent–this one can be a lot of fun. Pick an accent (hopefully one you’re not too good at) and read your work in that accent. It’ll entertain your brain and force you to slow down and focus. I often switch between French, Irish, and other accents while reading the same document.

Read aloud backward–this breaks our natural tendency to fall into the same rut. You can start by reading the last sentence of a paragraph and work backward from there.

Make it unfamiliar–the article above (https://www.wired.com/2014/08/wuwt-typos/) recommends “Change the font or background color, or print it out and edit by hand.” ” . . . if you want to catch your own errors, you should try to make your work as unfamiliar as possible.” It’s helped me to change the font style or font size, though after a time I get too familiar and have to change it again.

Print it out and edit by hand-repeated from above but it deserves its own line.

Use software–I use the free version of Grammarly as part of my checking process. Other software abounds.

Try different passes–I got this from David Farland. When he edits, he does specific passes through his manuscript: one pass will be for making sure dialogue is ok; one pass will be to make sure specific characters are acting as they should. You can do similar passes for specific grammar and spelling issues.

Get fresh eyes–if it’s important, have someone else read it. We’re too blind to our own mistakes so at some point it’s good to have someone else look at it for us (at the very least we can ask for beta readers).

For blog posts, I have my own proofing process that includes reading aloud (switching up accents, sometimes using a pencil and enlarging the text), using Grammarly, then doing one final read before posting. Even still I make mistakes, but they’re much fewer because I have a system in place.

But how about you? How do you proof your work? What techniques have you heard about or used in your own proofing?

3 thoughts on “Proofing”

I was going to mention the “change the font” trick, because it forces the shortcut portion of the brain out of the way, at least on one read.

One possible trick is to carefully choose the first thing you look at on a new day. You only get completely fresh eyes/brain for a short time.

I will say that I, personally, find myself much more likely to skim rather than read on a screen, so moving away from a screen (or at least a different screen than the writing was done on) is probably a good idea.

For some deep thoughts on why our brains work this way, I suggest Thinking Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman. In that model, everything suggested in the post boils down to: avoid the shortcut heuristics of System 1 and engage System 2. What works varies, and the moment the brain finds a faster shortcut, a given technique may stop working.

Great suggestions! I’ve heard about that book a lot so it’s on my list of things to read eventually. Makes sense given how our brains work. Our bodies are somewhat similar where we need to mix it up at the gym to get full benefits, but there’s an even greater need to mix things up with our minds to stay focused!

You don’t really have to read the whole book to get the gist (although it’s a fascinating look at how we think), just the first couple chapters. A lot of the individual chapters are specific case studies, showing it in practice across a variety of scenarios, but the basics are in the first pages.

That reminds me — after reading it, I wanted to revisit it periodically just to keep it fresh. It’s past time to do so…

Comments are closed.