Families

Main Points

• Families are often left out of fiction to keep things simple, make characters sympathetic, force growth, and justify personalities.

• Leaving families out often curtails profound depth and interesting conflicts.

• Families provide longing, bitter-sweet love, isolation, tragedy, endearment, connectedness, responsibility, shared history/culture, meaningful side conflicts, can turn the mundane into the interesting (especially in fantastical settings), and are too often missing.

• Going beyond the familiar tropes of orphaned heroes or immediately killed off family can create more powerful stories.

Introduction

Families. They can be an exquisite source of love and pain, support and betrayal, happiness and sorrow. Generally, they’re a mix of all those or somewhere in between. Siblings compete for attention, fight to self-differentiate, and struggle to grow up. Each family has their own culture and are a world unto themselves. One of the earliest surprises is finding out another kid’s family is way different than your own. So much of our earliest dramas and conflicts involve our families, along with our joys and happiness. Yet in many fictional stories, the heroes and villains are bereft of families with almost no importance given to parents, siblings, grandparents, cousins, aunts, uncles, etc. Why?

There are straightforward reasons not to include families. However, there are loads of benefits to having families for your characters, and since families are often cut out of many stories, including them may make your story shine. I won’t claim that having families is always necessary. But I will say you should always consider including them.

Lone Wolf Syndrome Why most heroes go alone

One primary reason for the main hero/villain not to have a family can be summed up in one word–simplicity. Without a family, there are no ties to keep the hero down. They can go off adventuring without having to worry about the family farm, their aging parents, their younger/older siblings, or anything else. They have no responsibility to anyone other than themselves. This is often true when the main character’s family is immediately killed at the start of the story. The author wants readers to see them happy but doesn’t want to be bogged down with writing about additional characters. So out they go as fast as possible. That’s not unreasonable. Taking out a large number of characters early on means you don’t have to write as much later on.

Another reason for leaving out families is sympathy. If the main character is raised as an orphan, the reader will sympathize with that. After all, it sounds hard. If we see the immediate loss of their loved ones, readers may sympathize with that too (although this has almost become a cliché). In contrast, villains often don’t have families because the writer doesn’t want the reader to sympathize with them. After all, it’d be awkward if the Dark Lord had some weirdo brother or sister who knew silly stories about them as a child, or worse, parents who used to change their diapers.

Another reason for not including a family (or killing them off) is forced growth. If the hero is bereft of a loving family, they’re going to have to fend for themselves and learn about the cruelty of the world. This is what we see in films like The Lion King where the loss of a family member is meant to spur the character into maturity and growth. After all, if Mufasa was still alive, he’d just take of all the problems so he had to be removed.

The final reason is justification to explain why a character is the way they are: why the main character is moody or bitter, or why the villain got to be the way they are.

No Man is an Island Why family matters

John Donne wrote, “No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Each of us come from somewhere, even if that somewhere is a place we’d rather not visit. Each of us is connected down the line and has a whole roster of heroes, villains, and average people in our family legacy. And those connections can mean significant depth, beyond what we could achieve if we made a character into a solitary island.

Harry Potter is one of the best examples of the power of families. Families are everywhere. While Harry has a stereotypical story with a tragic background, his parents remain important throughout the entire series, so much so that they feel as if they’re alive. This heavily contributes to the feeling of longing, bitter-sweet love, and isolation as Harry desires to gain a family. Much of the early conflict has Harry dealing with his horribly abusive extended family. When he discovers Sirius Black is his godfather, we gain hope because Harry still has some living family (the wealthy, erratic, sort-of uncle who spent time in jail). Later on, we realize Sirius has his own family stories and squabbles, some which are extremely important to the plot. This makes us more endeared to him since we’ve seen how much Sirius had to overcome to be good.

Ron’s family shows the power families provide for connectedness and love: they take in a stranger like Harry, have little jealousies and pranks between sibling rivalries, the kindness or aloofness of parents. Several times, Ron has to take care of his younger sisters Ginny, but this show of real responsibility in no way diminishes from the plot, it adds to it. Their large family allows for meaningful side conflict, such as when Percy aligns himself with the Ministry of Magic instead of his family, leading to them not to talk to each other. Differing beliefs within a family is a real problem for many as evidenced by Thanksgiving dinners. The Weasley’s have real problems and real differences. Yet things like this aren’t often used in fantasy settings. But in Harry Potter we see weddings, birthdays, making beds, mothers making fusses, chores, and all sorts of the mundane aspects of family life made interesting partly through a fantastical setting, partly because the characters are fascinating. All of this serves to make the reader love the family all the more and become more emotionally invested (never a bad thing).

This vastly raises the stakes when Voldemort returns because so much is on the line: every member of the Weasley family becomes at risk; Hermione has to memory wipe her muggle parents for their own safety; parents are frightened of what’ll happen to their children in magic school. All of it feels worse because of how connected we’ve become to their respective families. Families also show us the trauma inflicted earlier, such as with Neville Longbottom’s parents being tortured, resulting in his grandmother raising him.

Almost every major character is portrayed in a family role of some sort. Draco is saved by his parent’s love. Their whole family is seen as less villainous toward the end. Even Voldemort isn’t left out. Much of his backstory and motivation involves him desperately wanting to belong to a family and being horrified when he realizes where he came from (then stamping out any memory of his family history). Harry Potter terrifically makes “no man an island” and this significantly builds reader engagement and enjoyment. I’d submit that Harry Potter wouldn’t have worked nearly as well on an emotional level without this huge investment in families.

Other fiction similarly shows this same power. One of the best conflicts of Battlestar Galactica is the rough relationship between Lee Adama and his father William, who is the commander of the ship (how’d you like to serve under your father when you blame him for the death of your brother? There’s some good conflict). Breaking Bad wouldn’t have worked half as well if it didn’t involve all the conflicts of a family (again, the mundane is made interesting in such things as the meth cooking father teaching his child to drive). The emotional impact of The Road comes from the father/son relationship of surviving an apocalypse. I was stunned playing Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus because it turned such a stereotypical action figure (William Blazkowicz) into someone deeply profound. How did it do that? We got to see the main character’s family backstory/history as a child raised by a brutally abusive, racist father and a kind Jewish mother (there’s an awful scene where your dad forces you to kill the family dog to toughen you up because he thinks you’re weak; much of this abuse explains why Blazkowicz became so hardened later on). Later on in the game, Blazkowicz confronts his father, who informs Blazkowicz he turned in his wife (Blazkowicz’s mother) to the Nazi’s years ago for money. It’s horrific but wouldn’t have been nearly as impactful if it hadn’t come from his own family (as an aside, throughout much of the game you fight Nazis side-by-side with your pregnant wife, which also helps raise the stakes). The TV show Shameless is all about a dysfunctional family where each character provides conflict for all the others. If there were no family, it’d just be a show about a young woman trying to make it on her own and it wouldn’t be nearly as interesting. The fact that the main character is the surrogate mother to all his younger siblings adds a huge amount of conflict to the show.

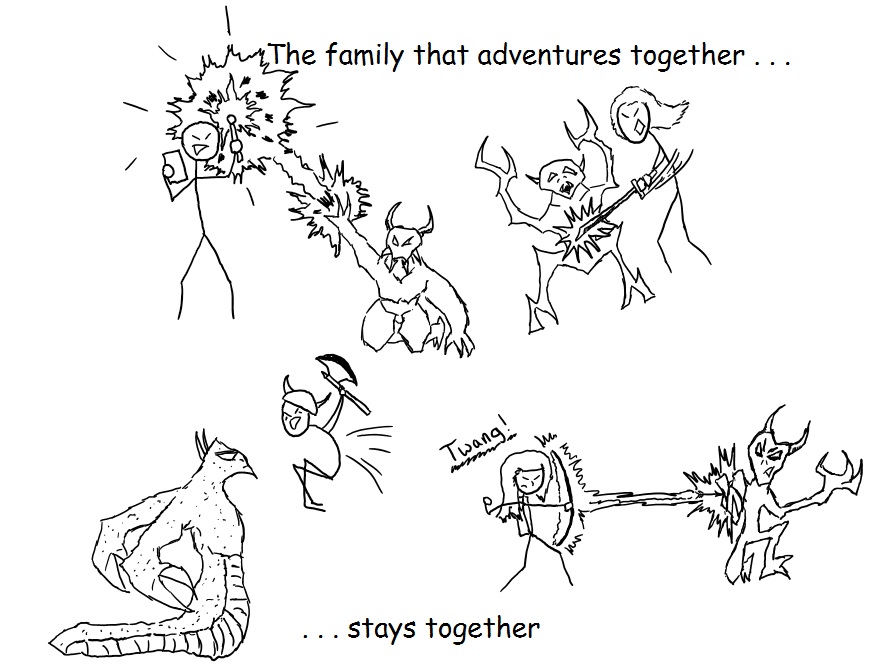

Hopefully, from this, you’ve seen some of the power that families provide (in connectedness, raising the stakes, meaningful side conflicts, etc.). The same can be true in almost any story, especially ones where the stereotype is for the character to be alone. So for your hero, could it be deeper if both their parents were alive and the hero had to worry about them? Could it add meaningful conflict if one of their siblings (younger or older) survived the initial disaster? Could an adventuring family be a possibility? (intact families like The Incredibles are rare, but that movie is incredible!) Instead of just having an tragic family history, could the main hero confront it somehow (meet their parents after a long time; reconnect with a lost/troubled sibling; be the lost sibling as opposed to the golden child; have to deal with some part of their extended family that cut their side off)? Can you flesh out what the villain’s family was like–siblings, parents, cousins, etc.? Could you have some of their family still be alive? Any of this will add worlds of dimension to your characters and world, despite what kind of family it is (single, divorced, widowed, nuclear, same-sex parents, multiparent, dynastic, polyamorous, extended, etc.). Families may not be appropriate for all stories, but they should definitely be considered for all of them.

But what about you? Why do you think many heroes are without families (either orphans or lose their families)? What familial relationships have you seen in fiction? Are the stories stronger with those relationships? Can you think of any stories that would be more interesting or stronger with familial ties?

2 thoughts on “Families”

It depends on the story. Frodo is Bilbo’s nephew, and Bilbo’s relatives (the odious Sackville-Baggins) are a major nuisance within the Shire portions of both The Hobbit and Fellowship.

I recently finished the first Mistborn book, and the young protagonist is an orphan (of sorts, her father’s alive but unaware of her), and her brother was recently killed. His voice and his warnings figure in, though, as she continues to “hear” from her memories of him and his lessons for living on the street.

You touched on some of the points I would have made on Harry Potter. I do want to add that the abuse coming from his aunt, uncle, and cousin makes it harsher, more personal than from, say, neglectful adults and mean kids at an orphanage. And that it’s sourced from Petunia’s jealousy of Lily (and that, post-Dementor incident, Dudley tries to make up with Harry but he doesn’t figure it out because he sees them through the meanness of past behavior and Dudley is lacking the ability to express anything well is itself a mini tragedy that’s sidestepped in the movies) just adds to it. When Harry realizes that Petunia is as affected by the heartbreak (she lost a sister when he lost a mother) as he is, but she hides it, is a major moment of growth for him. And another opportunity to show how much he cares, how much his heart and his compassion guide his decisions.

In Urban Fantasy, it seems that it’s more common for family to figure in. Kate Daniels’ nemesis is her father, October Daye was separated from her husband and daughter by an enchantment, but her mother, her sister (oops, spoiler), and others who helped raise her figure in to the stories, Mercy Thompson’s mom is absent but the pack that raised her is woven in.

My WIP has the main character, her husband, both of their parents (I’m still deciding on whether any of the parents are deceased yet), and their two children. On the personal and emotional side, all of those relationships play a role, and there’s a nice connectivity from that.

In Dragonsong/Dragonsinger, Menolly comes from a larger family, one that runs a (small) Sea Hold on Pern. Being so out of step with her family drives her decision to part, but it also makes the cutting of ties with them a much more conscious decision than you get with the usual orphan story.

It seems to me that a lot of complication can be added via family (and not just of the “my family’s been abducted by the villain!” variety). Sometimes, it almost feels like characters are designed without family specifically to simplify their story. Maybe we should all take a look, when developing characters, to see if isolating them so much is really the right path. There might be a stronger version of the same moments, once family is involved.

Agreed with all of that and thanks for sharing the examples! Families can add so much complexity to stories, it’s a shame they’re often left aside for the sake of simplicity. Stronger moments indeed!

Comments are closed.