Backward Forward Sideways Outlining

Main Points

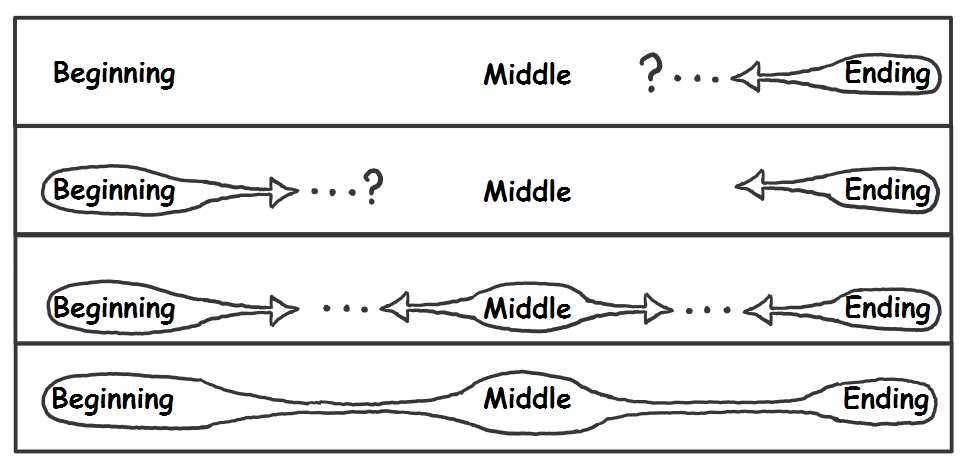

· Step one: start with a climactic ending, pick the emotional impact you want to create, then plot backward.

· Step two: when you get stuck, go to the beginning and plot forward keeping your ending in mind.

· Step three: when you get stuck, choose a middle and plot sideways (backward and forward from that point), trying to connect your beginning, middle, and ending sections.

· Step four: if you get stuck, pick other significant scenes in between your sections and use those to plot sideways.

· Ask yourself questions like “What has to happen to get to that point? What events do I need to include, or what emotional groundwork do I need to lay beforehand? What are the consequences of that point? What happens immediately after, or a little ways ahead?”

· Prospective hindsight is a powerful method we can use in our writing.

· Backward forward sideways outlining may not be for everyone.

Introduction

Outlining has been one of my main struggles in writing, something I’d like to improve to get my books out faster, with better quality, and less revision (see here). I recently tried a new outlining method and had great success so would like to share it since it might be useful for some newly budding authors.

Starting with the Ending Working backward, forward and sideways

The genesis of this started with Yoko Taro who uses backward plotting for his videos games, including the masterpiece Nier: Automata. Taro envisions a climactic/emotional ending, then builds backward from there. For Nier, the ending is two friends fighting to the death atop a tower, one blinded with rage, one sadly resigned to her fate. Who are these characters? Why are they fighting? What had to happen to get there? What events must occur to justify the sadness, betrayal, and awe Taro wants to elicit? Taro figures out those questions, little by little, going from Z to A until he’s at the beginning when the rage-filled character was innocent and happy, and the resigned woman was bent on her own revenge.

I often envision a climactic ending or some interesting scenes before I start a story, where great sacrifices are made, or horrific truth is revealed, or epic battles ensue. The benefit of backward plotting is everything builds into that ending point, whatever it may be. So I decided to try Taro’s method on one of the books I’ve been eagerly wanting to write. Since I’m a discovery writer, I discover most of my plot along the way. If I try to outline, the farther I get from the starting point, the more unclear things get. The same happened this time, only in reverse. I had the ending and a few chapters before, but not much else.

So I tried starting from the beginning. Again, I only made it a few chapters in before it became too nebulous to see where my characters were going. But a thought struck me. I had a scene in mind that could take place in the middle. What if I declared it the middle, then tried broaching out sideways from there? Maybe the middle portions would reach the ending and beginning.

I continued asking questions like, “What has to happen to get to the middle? What events do I need to include, or what emotional groundwork do I need to lay beforehand? What are the consequences of the middle? What happens immediately after, or a little ways ahead?”

It worked like a charm. I had a bunch of other orphaned scenes in mind that didn’t have a place to go. But now that I had these three anchoring points (beginning, middle, ending), the other scenes fell into place. I had an outline, it made sense, and I could start weaving side plots throughout it.

Why It Works Regular outliners may not need apply

Thinking backward in the right way can generate new ideas of how to get there, especially when using something called prospective hindsight. This comes from decision researchers Edward Russo and Paul Shoemaker, whose work is summarized in the book Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work by Dan and Chip Heath.

Consider the following from exercise from Decisive:

How likely is it that an Asian American will be elected president of the United States in November 2020? Jot down some reasons why this might happen.

Now try the next exercise from the same book:

It is November 2020 and something historic has just happened: The United States has just elected its first Asian American president. Think about all the reasons why this might have happened.”

As the Heath brothers relate, “when people adopt the second style of thinking—using “prospective hindsight” to work backward from a certain future—they are better at generating explanations for why the event might happen . . . The second scenario feels a bit more concrete, offering firmer cognitive footholds.”

Russo and Shoemaker’s research found that participants in experiments who were asked to use prospective hindsight created around 25% more reasons than the control group. In terms of plotting, having 25% more ideas could mean you finish your outline or come up with new or unique plot points.

I think that’s what happened to me. When I started backward (my first anchor point), I got a few more ideas than I had starting forward (my second anchor). Then when I got stuck, I set another anchor in the middle, and generated a few more ideas going backward and forward until all the sections met.

This can work for any number of anchor points, not just the three I used (beginning, middle, end). If you’re a fan of four section outlining, try this with all four anchors (I’d recommend the beginning or end of each section as an anchor). If you want five sections in your book, set five anchors and work sideways, starting with the ending. Or if you get really stuck, try it with as many scenes as you have in mind. You may be surprised with how many more ideas you generate and how your orphaned scenes start to coalesce into a thrilling whole.

Conclusion

Obviously this method isn’t for everyone. I have plenty of friends who outline just fine and would find this method overwrought and complicated. But for me, a discovery writer at heart, using these kinds of anchor points helped me flesh out the entire outline, see into the future, and create something impactful and understandable.

Books are individuals, so this might not work for all my books or yours. But what do you think of this method? Useful? Overly complicated? Helpful? Let me know in the comments below!

2 thoughts on “Backward Forward Sideways Outlining”

I outline iteratively, sometimes from scenes, sometimes from ideas, and sometimes I’m just massaging a seed until something interesting pops out. Takes me a while sometimes to fully outline a work, but it can be very creatively fulfilling.

…or you can do what I did in November, which was effectively writing a trilogy of novels as novellas. It’s much longer than a synopsis, but effectively let me go back and forth between “Fill this in with something cool later” and writing scenes I really wanted to write.

I also want to point out that Chuck Wendig had a really nice roundup of ways to outline: http://terribleminds.com/ramble/2015/10/06/how-to-outline-during-national-plot-your-novel-month/

…and an even more extensive (if less detailed) list of approaches here: http://terribleminds.com/ramble/2011/09/14/25-ways-to-plot-plan-and-prep-your-story/

And don’t forget, you can always use an outline to diagnose or fix story problems. It’s something you don’t always have to do up front, it could be something you do while you’re writing, or as a way to figure out how things link you, or to zoom out from the story so you can see what’s broken more easily.

…and it’s something you can continue to iterate on while you write.

I feel like the worst disservice done to my writing when I was younger was having an English teacher in middle school who taught us to outline linearly, and that it was a very fixed thing. The wildness of NaNoWriMo and many, many things said and written in podcasts, blogs, and conversations have all led me to recognize that outlining is fluid, personal, often unique to a specific project, and something that we each end up personalizing anyway.

Definitely true. Outlining, and writing in general, is a very fluid, individual thing. Thanks for sharing all your insights and helpful resources!

Comments are closed.