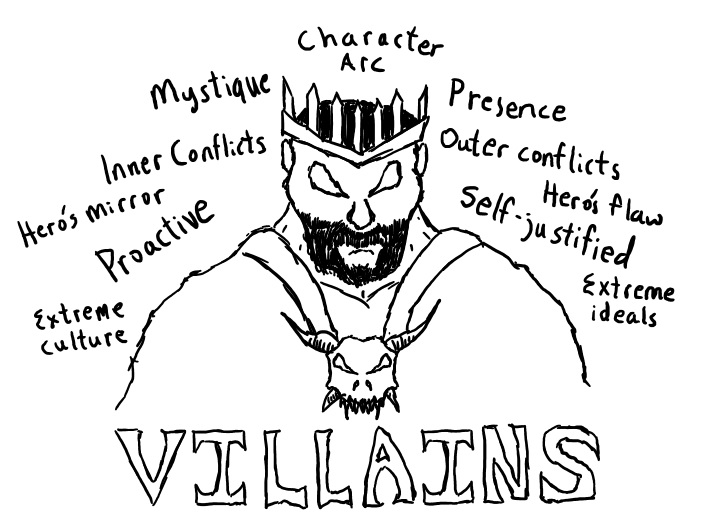

Masterful Villains

Main Points

• Great villains:

• Are proactive;

• Are sympathetic or have self-justified views, or unique motivations;

• Often come from wildly different cultures;

• Have as profound character arcs as the heroes and overcome their own internal/external conflicts;

• Have extremist ideologies or push positive/negative values to the extreme;

• Have wildly different perspectives and worldviews;

• Have immense mystique and presence;

• Powerfully mirror the hero’s journey/arc or are the negative fulfillment of the hero’s flaw

• Should be beyond regular villainous tropes.

Introduction

Villains are one of my favorite things about fiction: watching the conniving master of darkness work their evil plans, thwarting the hero at every turn. Villains are a delight, one that many readers share, so much so that anti-heroes and stories of good guys turning evil have risen in popularity. “A hero is only as good as his villain,” so the refrain goes. Great villains help highlight themes, provide meaningful tension, force character growth, kickoff the story, and are just plain fun to watch.

But what makes a villain great? I’ll share my thoughts on masterful villains, drawing from a large range of different examples. I wouldn’t suggest trying to implement all the following in one book but it might be good to consider trying on a few. I’ll put recommended playlist questions appropriate.

***SPOILERS FOLLOW***

Villainous Traits Inspiration from Evildoers

Proactive. This is probably my favorite thing about villains. They’re utterly proactive. In contrast, many heroes start off as reactive, only engaging in the main plot when the villain shows up and does something to rock their world. In general, the villain has a goal, a plan, and they take action to fulfill their desires. Whether they want to rule the world, kill everyone or something in between, villains are masters of their fate. Is your villain proactive? What’re their immediate and long-term goals? Can you make your main characters more like villains in their proactivity and goal making?

Sympathetic/Self-Justified Views/Unique Motivations. Some of the greatest villains I’ve seen are sympathetic or in the least have self-justified views. We understand why they do what they do, even if we don’t agree with their conclusions. “The villain is the hero of their own story,” shouldn’t just be a platitude, it should be true. What’s the villain’s story? Why do they do what they do? Whatever their reasons, it should make sense to them. This is something I wish I’d seen more with Darth Vader. He says his motivation for his actions is to bring order to the galaxy but we don’t see much of his turmoil at experiencing chaos (beyond losing his mother). Instead, his motivations at the end of Revenge of the Sith seems more like an angry teenager who believes he’s gone too far to be redeemed.

It’s better to go beyond the normal motivations of “they’re just evil and got minions from Minions R Us.” A great example of this is Killmonger from the recent Black Panther film. He’s sympathetic because we see his pain, growing up fatherless and disinherited from his homeland, forced to wade through suffering when Wakanda enjoys peace. While we may not agree in his views (that the disenfranchised should be armed to rule over their oppressors), we see how he got to that belief, and why he feels justified in his actions. Another powerful example is Bill Crowley, the demon in I’m Not a Serial Killer who kills to maintain a functioning mortal body so he can remain married to his elderly sweetheart. I was surprised when I first read this book, because I thought the villain was acting purely from evil motives. His love for his wife is understandable and makes him more sympathetic/engaging even while his actions are horrible.

A villain rarely works as being “evil for evil sake,” (except in the case of psychopaths like Hannibal Lecter). A villain may believe they’re saving loved ones, preventing greater disaster than they’re causing, fighting for the greater good, or they’re trying to save themselves. If you can find a unique motivation, it’ll stand out. An example for this comes from the Prince of Nothing series by Scott Bakker. In it, there’s a race of demon like creatures called Inchoroi. From the wiki-page:

the goal of the Inchoroi is to prevent the eventual eternal damnation of their souls by severing the connection between the World and the Outside. They believe this can be accomplished by reducing the number of souls in the world below 144,000. They attempted this on many other worlds, prevailing each time only to find themselves still damned, before the Incû-Holoinas crashed into Eärwa, which they view as the land of their redemption.

http://princeofnothing.wikia.com/wiki/Inchoroi

There’s a lot of interesting reasoning behind this that plays out in his novels. So, what motivates your villain? How can you make them more sympathetic? Would it be more powerful if they were sympathetic? How do they justify their horrible acts and sleep well at night?

Cultural Differences. Some villain’s motivations may come largely from their culture. The Nazis believed in the superiority of the Aryan race, justifying their actions. The Japanese treatment of American prisoners of war can be greatly explained because of differing cultural views of surrender (the Imperial Japanese saw surrender as cowardice worthy of brutal mistreatment whereas American soldiers saw surrender as honorable). Manifest Destiny was used to justify the United States’ expansion across North America by whatever means necessary. While these examples are much more complex than my short summaries here, the point is that cultural beliefs have been used to justify atrocities throughout history. Many times, villains come as much from their culture as they create it. What kind of cultural inheritance could make your villain evil? What current or past cultures have contributed to horrible actions?

Character Arcs/Overcome Conflicts. Many of the best villains have strong character arcs, whether within the story or as part of their history. One prime example is Darth Vader. His redemptive arc (from the original trilogy) sees him start out at point A as a monster willing to kill subordinates for failure and uncaringly watching worlds destroyed to point B where he’s willing to betray everything he’s built and fight to protect his son. His arc makes Darth Vader one of the greatest villains in fiction. He wouldn’t nearly be as powerful without that arc.

Overcoming conflict (internal or external) can also make a villain great. President Snow (The Hunger Games) has to poison his way to make it to the top, with recurring consequences for his actions. Voldemort (Harry Potter) has to journey all over the world to recover artifacts sacred to him as well as extinguish any memory of his true past. He also contends with starting out with little and having to learn everything about magic from scratch. Killmonger (Black Panther) becomes conflicted about his plan when he has a vision of his father. Gus Fringe (Breaking Bad) has to battle a Mexican drug cartel and barely secures victory over them. This conflict comes incidental to his fight with the main character, Walter White. This endears Fringe to viewers as we witness his accomplishment, and it makes his ultimate defeat by Walter all the more powerful. This has the secondary effect of making Fringe look even more powerful as a villain because of what he overcame. Similarly, Vader looks more powerful because we know how strong the Jedi were and he hunted them down.

Real life dictators always have to deal with internal power conflicts, such as Hitler in The Night of the Long Knives where many threats to his power were assassinated. For a great discussion on examples and how this works, I’d recommend, The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith. It details how dictators deal with the constant threat of coups (buying off coalitions of the most influential supports, always having enough funds to pay the military, etc.).

What character arcs could our villains go through? What’s their point A and point B (whether within the story or before it)? What internal conflicts do they have to overcome that are outside the main heroes? What enemies have they defeated to cement their power?

Extremist Ideologues/Extreme Values. Often, villains come from extremist points of view. In the video game Hydrophobic, the villains are Malthusians who kill as many people as they can to prevent overpopulation (their slogan is “Save the World – Kill Yourself”). In the game Bioshock, Andrew Ryan radicalizes his beliefs of free markets, individualism, and capitalism (the game’s setting is a blown up version of Ayn Rand’s objectivism). The Joker is the embodiment of anarchy or nihilism. Evil values or positive values work just as well. Javert from Les Misérables is a masterful antagonist because of his extreme obsession with justice, normally a worthy attribute. Just about any principle, virtue, system of philosophy, belief, non-belief can be turned evil by extremism and radicalization. Having an extremist point of view can make a villain pop and become unique and original.

A word about religious extremism, however. Religion is often used as the easy-go-to justification of atrocities without addressing the complex nuances of faith. Even in some of the most abusive religions, there are people who feel they gain real benefit and inspiration from their beliefs. They may ignore rampant corruption, but they feel the truth of their cause and see miracles in their own lives. If we use religion as a cause of villainy, we should include some of these nuances, including people who are helped by their beliefs.

What potential belief system or philosophy could the villain take to the extreme? What good principle (or bad one) could they twist into something awful? Can you think of how an extreme version of courage, compassion, prudence (or other good virtues) could be turned evil? How can you show a more nuanced version of religion if that’s the motivation behind extremism? How do actual people from extremist groups feel about their faith? (one profound example of this is the book Terrorists in Love: True Life Stories of Islamic Radicals by Ken Ballen, which highlights the complexities that go into creating suicide terrorists)

Wildly Different Perspective. Many of the greatest villains are fascinating to watch because of how differently they view the world. The Joker in The Dark Knight is a perfect example. He’s chaotic, says incredibly insane (but at times honest) and profound things. He views the world outside our regular perspective. In speaking to Batman, he relates:

To them, you’re just a freak, like me! They need you right now, but when they don’t, they’ll cast you out, like a leper! You see, their morals, their code, it’s a bad joke. Dropped at the first sign of trouble. They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these… these civilized people, they’ll eat each other. See, I’m not a monster. I’m just ahead of the curve.

His crazed perspective draws in the viewer, begging us to wonder, “Why does he see things that way? What is he seeing we aren’t?” It’s fascinating how he regards normal life.

Another great example of this is Light and L from Death Note. Both have extremely unique ways of looking at the world–Light sees everything as a potential chess piece in his master plan to manipulate and use, while L views everything through blunt and coldly analytical eyes. We love House because of his different way of looking at things, the same as we love Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock as an almost sociopathic investigator. Can we include unique perspectives for our villains? Can we make them see the world entirely different from most society? Would that draw the reader in?

Mystique/Presence. Similar to different worldviews, great villains often have great mystique or presence. Their hidden nature makes us want to learn more about them. Or something about them spells dread. In Jim Butcher’s Storm Front, the villain draws power from natural storms to commit murder. When we realize this, every storm creates a sense of dread (“Oh no! The villain is going to do something totally evil!”) The Joker (The Dark Knight) has an incredibly powerful presence and mystery about him. We never know what he’ll do when he’s on screen. His mystique is encapsulated when he talks about his scars, each time sharing a different version of how he got them. With Voldemort, no one can say his name. He’s so evil he’s “He Who Must Not Be Named.” President Snow (The Hunger Games) always smells of roses. Darth Vader dominates every scene with the sheer force of his presence. What can we add to our villains to increase their mysteriousness or their presence? What emotions are we trying to evoke when they’re in the room–fear, domination, flinching?

Mirror to the Hero/The Fulfillment of the Hero’s Flaw. Often, the villain is set out in stark contrast to the hero. In Star Trek: Nemesis, the villain is a clone of Captain Picard, who was twisted by his horrible upbringing to become a monster. At the end, Picard questions whether or not he’d be the exact same evil maniac had he been born in similar circumstances. Killmonger (Black Panther) is almost an exact replica of T’Challa (both are royalty, both lose a father unjustly, both seek the ‘good’ of their nation) but Killmonger was left to rot by himself without the loving support T’Challa had. T’Challa is forced to question whether or not he’d become the same if left in the same circumstances. “There but for the grace of god go I” is a powerful way to match a villain with a hero. Often, the villain and the hero have the same fatal flaw and the villain becomes a reminder of what the hero will become if they’re not careful. Can you somehow tie in the main character’s growth with the villain’s? Can they be mirrors of each other?

Beyond Tropes. One common problem with villains is making them ugly, deformed, or otherwise stereotypical. Many of Dan Brown’s stories have this problem, where the evil villains are disabled or disfigured. Most of Ayn Rand’s villains are ugly and whiny whereas the heroes are beautiful and confident. Similarly, a lot of backstories of villains involve some sort of trauma where they feel justified in hurting others. But there are so many people who suffer trauma who don’t lash out with their pain (something like this could be great potential for mirrored heroes/villains). We should go beyond these tropes to create more realistic villains and heroes, drawing them out of a vast array of possibilities instead of just stereotypes. Can you turn a stereotype on its head for your villain? Would it be more powerful (and more terrifying) if you made them the loving family man instead of the bitter loner? Could the villain have suffered deep trauma but act evil for an entirely different reason? Could there be a mix of beauty and confidence distributed between the villains and heroes to add more depth?

Conclusion

Hopefully, some of this is useful in creating unique and powerful villains. As I wrote earlier, villains tend to be one of my favorite parts of fiction. Often, the most disappointing aspect of a film or book is when the villain is hyper typical and generic. So create great villains, and they’ll help create great heroes.

But what about you? Do you have any favorite villains? If so, what them makes them so special? How do you create great villains?

3 thoughts on “Masterful Villains”

A villain should still be the hero of his or her own story.

I liked an observation I heard once: in a Campbellian sense, the Hero and the Villain are on the same journey, except the Villain doesn’t get the turn to victory at the end. It doesn’t always apply, but it’s an interesting way to think about it.

That being said, the stuff I’m writing now doesn’t have one villain, it has an organization. So, villains can fall by the wayside, but there’s a source for the next antagonist and some long-term goals.

I just hope to not fumble it the way BSG did with “…and they have a plan”.

That is one of the biggest problems of BSG, the allusion/promise to an overarching plan that never actually materialized. Evil organizations can be a lot of fun and that’s a pretty realistic route to take. Systems often churn out villains more than personal choice.

It also opens the possibilities for defections and redemptions from the enemies, and betrayals by one’s purported allies, all without losing the impact of the overall opponent.

Comments are closed.